What Sort Of Perspectives Are We Born With Compared To The Ones That Are Learned

Abstract

In this study, we investigated children's perceptions of their learning experiences in early childhood didactics and care using data from two unlike settings: Brazil and Finland. We adopted a qualitative and cross-national research design. Photographs were used to get together children's representations of their learning places and spaces and also later to elicit reflections during group interviews. This process of using photographs allowed u.s. to elicit children's perceptions about their learning. The analysis consisted of content categorization of the photographs, content analysis of the interviews, and juxtaposition of materials in a comparative framework. The children represented and conceived their learning experience in four categories of school spaces: objects, actions, significant others, and cultural practices. By analyzing each of these categories, nosotros place five core elements of children's perceptions most their learning: relevance of peer interactions; recognition of learning through play; children's acknowledgment of their own competence for learning; school spaces as places for learning actions; and present time every bit the timeframe for learning. Practical implications of these findings are discussed, including the importance and relevance of considering children's perceptions.

Résumé

Dans cette étude, nous avons examiné les perceptions des enfants de leurs expériences d'apprentissage dans les services d'éducation et de garde de la petite enfance à l'aide de données provenant de deux milieux différents: le Brésil et la Finlande. Nous avons adopté united nations devis de recherche qualitatif et plurinational. Des photographies ont servi à recueillir les représentations des enfants de leurs espaces d'apprentissage et également, à un stade ultérieur, à susciter des réflexions chez les enfants lors d'entretiens de groupe. Le processus d'utilisation de photographies nous a permis d'obtenir les perceptions des enfants de leur apprentissage. 50'analyse consistait à catégoriser les photographies, analyser le contenu des entretiens et juxtaposer le matériel dans united nations cadre comparatif. Les enfants ont représenté leur expérience d'apprentissage dans quatre catégories d'espaces scolaires: les objets, les actions, les personnes significatives et les pratiques culturelles. En analysant ces catégories, nous avons identifié cinq éléments fondamentaux de la perception des enfants de leur apprentissage: la pertinence des interactions entre pairs, la reconnaissance de l'apprentissage par le jeu, la reconnaissance par les enfants de leur propre compétence d'apprentissage, les espaces scolaires comme lieux d'actions d'apprentissage, et le temps présent comme cadre temporel d'apprentissage. Les conséquences concrètes de ces résultats sont discutées, notamment l'importance et la pertinence des perceptions des enfants de leur propre apprentissage.

Resumen

Este estudio investigó las percepciones de niños sobre sus experiencias de aprendizaje en los primeros años de educación en la escuela y centros de cuidado infantil, utilizando datos producidos en dos contextos diferentes: Brasil y Finlandia. Se adoptó un diseño cualitativo y cruzado a nivel nacional. Se utilizaron fotografías para recolectar las representaciones de los niños de sus espacios de aprendizaje, y así mismo, para captar sus reflexiones durante entrevistas en grupo. El uso de fotografías permitió a los investigadores captar las percepciones de los niños sobre su aprendizaje. El análisis consistió en categorizaciones de fotografías, análisis del contenido de las entrevistas, y yuxtaposición de materiales en united nations marco comparativo. Los niños representaron sus experiencias de aprendizaje en cuatro categorías de espacios en la escuela: objetos, acciones, personas especiales y prácticas culturales. El análisis de estas categorías permitió la identificación de cinco elementos principales en las percepciones de los niños sobre su aprendizaje: importancia de sus interacciones con compañeros; reconocimiento del aprendizaje a través del juego; reconocimiento de los niños de sus propias competencias para el aprendizaje; espacios escolares como sitios de aprendizaje; y el ahora como marco temporal de aprendizaje. Este estudio también analiza las implicancias prácticas de estos hallazgos, incluyendo la importancia y relevancia de las percepciones de los niños acerca de su aprendizaje.

Introduction

Studies focused on exploring children's perspectives have gained prominence since the late 1990s. In general, such studies have identified children as of import contributors to the investigation of their own reality. Listening to children's voices enables researchers to understand social phenomena with greater clarity (Sant'Ana 2010) and to access an entirely new earth of meanings near the lives of children (Trautwein and Goncalves 2010; Pálmadóttir and Einarsdóttir 2016). Colliver and Fleer (2016) argued that understanding young children's perspectives tin can provide educators with concrete information to effectively guide their practices toward improving children'due south learning outcomes, as expected by contemporary curriculum frameworks beyond the globe.

Nevertheless, when it comes to defining learning and reflecting on its processes, younger children accept been historically left out of this conversation. A substantial body of research argues that young children are incapable of agreement what learning is and reflecting on their own learning process. Metacognition is considered to exist an ability that does not develop in children who are less than four years of age (Larkin 2010; Powell et al. 2011). Additionally, current studies in the field of early childhood instruction and care (ECEC) prefer to investigate learning by focusing on its outcomes, which are specially linked to the effectiveness of educational programs or practices aimed at the acquisition of specific knowledge or skills (Burger 2015; Goodrich et al. 2017; Helal and Weil-Barais 2015; Landry et al. 2017). For such reasons, the focus on children'southward perspectives of their learning experiences is not a topic that has been extensively explored.

We consider it important to understand learning processes from the perspective of children. Similar to the significant advances that have been made to overcome the methodological challenges in children's participation in research (Clark 2005), we believe that efforts should exist made to reduce the conceptual gaps betwixt adults' acknowledgment of children's competence and empathise children's perspectives virtually learning.

In this study, we accost learning from the perspective of experience, which is divers past Larrosa (2002) as something that happens and transforms us. The learning experience is a procedure by which situations are able to influence the way we are constituted in a sure time (moment of life) and space. Therefore, a particular focus is given to how the contextual elements play a role in defining the learning experience. Equally learning can happen in different social contexts, time, and infinite, in this study, nosotros clarify that we are interested in the learning experiences in ECEC context and in the school as a learning infinite.

We investigate children'southward perceptions of their learning experiences in the contexts of early childhood teaching (i.e., daycare centers or schools) past addressing the following enquiry questions:

- one.

How do children perceive their learning experiences in ECEC settings? What ideas do children use to express what they sympathise of their ain learning experiences?

- 2.

What associations exercise children establish between their learning and the spaces in which they learn in ECEC contexts?

- 3.

To what extent do cultural differences influence how children perceive their learning experiences in ECEC?

Schoolhouse as a Learning Space

To reflect on the idea of learning spaces in ECEC, nosotros draw on Soja'due south (1996) concepts of Firstspace, Secondspace, and Thirdspace, which offering a more multidimensional and relational idea of space and bespeak to an integration of human and environmental constituents. According to Soja (1996), infinite is not identified or divers solely by its material elements or geographical position; infinite has different dimensions, all directly related to culture, ideology, social rules, values, and man activity. Soja's interconnected dimensions of Firstspace (i.due east., concrete structures that compose the surround), Secondspace (i.e., personal meanings near the physical environment), and Thirdspace (i.due east., cultural and social aspects that influence private interpretations of space) are primal and continued to the individual. This understanding of space highlights how homo activity creates and defines space; at the same time, infinite provides affordances to certain actions in a dialectic process of constitution.

When nosotros rely on these concepts of space to reflect on the learning experiences of children in ECEC, we recognize that children are a part of the construction of ECEC spaces and vice versa. Previous studies addressing children'due south perspectives of school space accept focused on the use of physical infinite (Einarsdottir 2005), children'south participation in the process of space construction (Vuorisalo et al. 2015), and children's agency in certain spaces or learning environments (Emilson and Folkesson 2004). Such studies take shown how adults and children relate to space jointly, and how children play an important function in defining the use of materials and physical spaces. The findings call for increased participation of children in the decisions that affect their schoolhouse routine and the importance of because peer relations in the context of ECEC. Even so, they do not accost questions on how children live and understand their learning in the schoolhouse space. Therefore, instead of examining the physical space, our aim is to focus specifically on the process of meaning making past which the experiences of learning are signified while in the school space. We aim to understand these experiences as the element that transforms the school in a learning space.

In line with the notion of Thirdspace, it is possible to focus on individual learning experiences and explore possibilities that a certain environment (in this case, ECEC) in different cultural settings offers for learning processes. In this sense, children's representations and perceptions of the school space reveal elements of their subjective and social life and experience, and these elements are office of how this feel is produced and negotiated in a shared process.

Methods

Study Contexts: Brazil and Finland

In Brazil, as in Finland, ECEC is recognized as a universal right of all children since birth. Rutanen et al. (2014) have highlighted similarities between the two countries regarding the key value of human being nobility, the understanding of the child's right to life and full development, and the upholding of the child's right to daycare services before compulsory schooling.

In Brazil, ECEC is governed by the Child and Adolescent Statute (ECA, Ministry of Education of Brazil 1990) and the Constabulary of General Guidelines for Teaching n. 9.394\96 (Ministry of Education of Brazil 1996), and this service is to be provided by daycare centers (0–3 years erstwhile) or pre-chief schools (four–5 years old) under the pedagogical responsibility and budgetary administration of the municipalities (Ministry of Education of Brazil 2006). According to the Brazilian National Curriculum Guidelines for Early Childhood Pedagogy, ECEC should provide the conditions to ensure recognition, appreciation, respect, and interaction amid children, promoting their integral evolution and respecting their individual needs (Ministry of Education of Brazil 2010). Like in Brazil, Finnish ECEC is regulated at the national level, but municipalities are responsible for its organization and provision (Human action on Early Childhood Teaching and Intendance 2018/540). In Finland, ECEC is based on an integrated approach to educational activity and care, the so-called "educare" model. Finnish legislation defines ECEC as a planned and goal-oriented entity of education, nurture, and care, with an emphasis on pedagogy.

Yet, despite a similar agreement of the role of ECEC in the child'southward development and recognizing it every bit a universal right of all children, Brazil and Finland accept materialized this service in very distinct ways. While in Finland the participation rate in the adequately equal and homogenous ECEC system is around 75% among the 3–v-year-olds, in Brazil this figure is still below 50% (INEP 2016), frustrating the expectations in the National Plan for Education (Ministry of Education of Brazil 2016). Additionally, in Brazil, the entire educational system is plagued past social inequality and inequity, which results in different ECEC services according to locality, income, and race. Admitting it is axiomatic that both nations face different issues, it is too true that they aim to heighten children's participation (Santos 2010; Carvalho et al. 2009) and share the business to find innovative ways to promote pregnant learning while avoiding "schoolification" of ECEC. There is a pregnant investment on reviewing internal policies and practices (Hietamäki et al. 2017; Simões and Lima 2016), which by culturally contextualizing international debates on ECEC, Brazil and Finland have evidenced their commitment to diminish social inequalities past investing in quality education. Therefore, the rationale of choosing these countries is that we recognize and value the distinct cultural characteristics of Brazil and Finland, interpreting them as an element that can enrich the investigation of a complex phenomenon such every bit the learning experiences of children.

Methodological Approach

This study adopted an abductive process of reasoning (Okasha 2002) in which scientific thinking prioritizes information that comes from data rather than seeking to confirm a specific theoretical hypothesis. Furthermore, we base the analytical process on the principles of qualitative methodology presented past González-Rey (2009). These principles focus on the study of subjectivity by considering the constructive–interpretative and singular grapheme of the product of scientific noesis and by understanding research as a dialogical process. The constructive–interpretative methodology allows a nonlinear relation with the field of research and its participants. Information are not taken from the participants, only rather produced and interpreted considering reflections, dialogs, and an entire communication arrangement that grants centrality to those involved in the research (González-Rey 2014). Thus, we let for the non-standardized in the context of research, emphasizing the quality of the information produced and placing the researcher in the midst of interpretations. In the following sections, we outline the fashion in which we undertook this methodological path.

Participants

The participants consisted of forty 3–vi-year-old children from one ECEC school in each land. Participants were randomly selected from a total of 225 and 52 children in the Brazilian school and the Finnish daycare center, respectively. Children were only included if they manifested a wish to participate in the report and if their parents consented to their participation. It is important to add that both ECEC schools had children from dissimilar social backgrounds, which resulted in a heterogeneous grouping of children. In the Brazilian context, cultural diversity is a characteristic characteristic of the guild, and the different socioeconomic backgrounds of the children added to this heterogeneity. In the Finnish context, diverse economic backgrounds contributed to the heterogeneity, in this case, because there has been a significant increment of foreigners in the educational system. Thus, the sampled groups included children from different classes: middle, low-income, and upper-center.

Ethical Considerations

The ethical committee of the Federal University of Uberlândia (CAAE 43646815.ii.0000.5152) and municipal regime approved this report. In line with the guidelines of responsible and upstanding enquiry with human beings, data containing the real names of the children or the school were kept confidential. Children'southward names were replaced by fictitious ones, and pictures containing images of people (e.g., other children, teachers, or staff members) were altered to prevent identification. To ensure that the parents of all children involved were enlightened and supportive of the research, formal written consent agreements were obtained. Additionally, children were consulted and took office of the report simply if interested. They were too able to get out the written report whenever they wanted.

Data Collection

Participants were divided into iii groups of six to seven children according to their age (3–4-year-olds; 4–5-yr-olds; and 5–6-year-olds) for the discussion groups. Data were then collected past a two-step process, which was practical in both settings similarly. The first step explored children'south representation of the connections they created between learning and the spaces that they used, constructed, and lived in the school. This procedure consisted of a group session in which children were invited to talk about what it meant to learn in schoolhouse, and immediately after to walk around the school and photograph the spaces, objects, people, or situations that they thought were related to learning. Photographs have been used in sociological (Allen 2012), psychological (Blackbeard and Lindegger 2007), and educational studies (Harcourt and Mazzoni 2012; Loughlin 2013). They are a powerful tool to capture individual representation, enabling, for case, children to present their views through a means of other than just linguistic communication (Clark 2005; Cook and Hess 2007; Einarsdottir 2005). During the walk around the schoolhouse, in pairs, children could autonomously employ the photographic camera (provided by the researchers) and were permitted to accept as many pictures equally they liked (67 in the Brazilian groups and 250 in the Finnish groups). Later on, the researchers organized these photographs and excluded the ones that had exactly the aforementioned content. Thus, each group from each country had near 10–xxx pictures.

In the second footstep, children'southward reflections about the learning processes and the contents in those item spaces photographed by them were sought. In this case, photography was used as a tool to institute a dialog with the children, contextualizing the content of their perceptions, and allowing their voices to be expressed. For this footstep, researchers conducted a group interview session and used the chosen pictures of each group to initiate the word. They guided the reflections with using questions such as: Why did you choose this motion-picture show? Where are you? What happens when y'all are in this place? What can you exercise in these places? Do y'all think you are learning something when you are in that location? What would that be? Who are you lot with when you are learning?

The interviews with the children were audiotaped and transcribed for the content analysis. All data drove procedures were administered to each group of children separately; and it is important to note that the same research protocols and instructions were used in both countries.

Analysis

The information collection generated 2 dissimilar sets of textile for analysis: children'south pictures and the transcripts of children'southward reflective narratives. We focused only on the most obvious meaning of the pictures, without applying any technical or artistic measurements (Thinker 2013). Through this process, nosotros created a map of children's representations in each age group according to the following categories that emerged from the analysis process of the content of the pictures: (a) inside/outside and (b) object, person, place, and scene (i.east., place with people doing something).

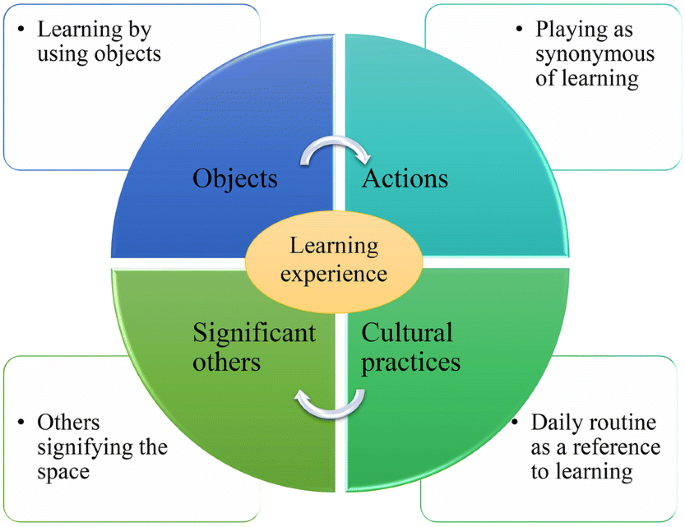

Next, content analysis was used to examine the interview transcripts of all the groups. Thought the report used an abductive arroyo, questions were used as (pre)structured topics to guide the interview. The dimensions for the analysis were as follows: (a) Where I learn; (b) What I learn; (c) When I learn, and (d) Who I learn from/with. Thus, the coding procedure involved identifying elements that were directly related to these themes. The results were grouped into iv categories that emerged from the content analysis, revealing how children perceive their learning experience in those particular school spaces: objects, action, meaning others, and cultural practices.

To ensure thoroughness in coding, both materials were analyzed first in the state of origin (Brazilian data analyzed in Brazil and Finnish information in Finland), and subsequently, by the partner country. However, for juxtaposition of the data and cross-cultural understanding of the phenomenon, we added another phase in which the whole corpus was discussed by a multicultural group of researchers. In this process, we analyzed divergent results and incorporated translations of cultural elements that were essential to contextualize and understand each dataset. While cross-cultural comparison only shows differences and similarities, juxtaposition allows their integration, revealing the core elements of the phenomenon.

Results

The first steps of the information assay resulted in a map of children'southward representations (run into Table ane). This map shows how the children in each age group in each land represented the relations between the learning experience and school space with their pictures.

Brazilian children represented their learning experiences with pictures that chiefly focused on objects or places. Pictures of objects included swings in the playground, stairs, taps in the toilet, books from the library, plants from the greenhouse, and decorations in the classroom. The places registered by the children covered not simply their classroom, playground, and yard but as well the deli and the green area that surrounded the school, which the children referred to as the "magic forest." This variety of images suggests that the children understand their learning processes equally something that also happens outside of the traditional classroom environment; the processes do not relate exclusively to academic activities structured by the teacher.

Finnish children also represented their learning experiences by mainly focusing on objects and places. Indoor places registered past the children included entrance halls, toilets, corridors, and rooms for diverse activities, such equally sleeping, gymnastics, handcrafts, and forenoon circles. Outdoor places represented in the pictures consisted of the playground and the yard. Among the pictures of objects were chairs, tables, beds, smart boards, books, materials for handcrafts and morning time circle activities, letters and written rules on the wall, shoes, and coat racks. In addition, objects used in physical exercises such equally outdoor slides and indoor ladders were captured. Pictures taken by the three-year-quondam children, to represent their learning experience, too featured other people (children taking photos with an iPad). In dissimilarity, the pictures taken by 6-yr-former children more frequently featured various pedagogical objects such as letters and smart boards. This variety of elements photographed conveys that the children understand their learning as something that tin happen everywhere in the daycare eye, in the material spaces bachelor to them.

Further, the analysis of the interview transcripts yielded four response categories that summarized how children perceived their learning experience. We represent these categories in Fig. one, and in the following section, we use them to exemplify children's perceptions along with excerpts from the original datasets.

The four categories that emerged from the data, which revealed how children perceive their learning experiences

Category 1: Objects

Objects often appeared in the children'due south pictures, and their narratives revealed the connection between the learning experiences and the objects in school, both indoors and outdoors: "This way… hmm, like we are going to slide and then to swing and … with ane foot go bouncing all the way to the floor." (Anna, 5 years quondam, referring to the pictures with the slides). Additionally, children referred to their learning experiences when using the various tools designed to create a child-friendly pedagogical environment, such equally slides, smart boards, or specific elements from the schoolhouse infrastructure, such as stairs and water taps in the toilet: "Climb to the ladder and … leap off it and then I don't know … Still… Oh well… I'm going to do such balancing things, I do non think what they are chosen." (Terhi, 4 years old, referring to the picture show of the ladder).

These narratives showed how the objects that etch different places of the school environment are part of the whole, and when in contact with these objects, each child can signify them according to their own atypical experience, which on many occasions can transform the functionality of the object. For example, children from G2—Brazil represented a learning situation by taking a picture of a pole used to hold up a volleyball cyberspace in the thou. During the interview, the children described the object as the pole that they used to learn how to climb: "… It is the stick we climb, there we learn how to climb on" (Maria Clara, iv years one-time); "Nosotros learn to go up and down… yes… there is a stick that we climb" (João Paulo, 4 years old); "Information technology is a place of many friends" (Jennifer, iv years old). Thus, the objects that compose the dissimilar spaces of the schoolhouse are signified in a singular way, depending on how the children produce experiences when in contact with them.

Another important aspect of this category concerns the quality or the characteristics of the cloth surround. At no point did the children refer to the appearance of the objects or places (e.g., an ugly or damaged toy, old article of furniture, or a beautiful room). The possibilities that a detail space afforded were pregnant from the viewpoint of children'southward learning feel. In many situations, the children described the pregnant of a learning feel based on what they were able to do with that object or in that specific place: "I think that I am learning to do many sprints considering when we run in that location we take such a long path; this lane is huge" (Arthur, 6 years old, referring to the moving picture of the running runway in the yard).

It was as well axiomatic that the children expressed and connected diverse meanings to the same objects and places. The post-obit discussion between 6-year-olds and their instructor illustrates how the hall was interpreted both every bit a space for constructing activities and as a space to learn the school'southward social rules:

-

Teacher: What does this motion-picture show mean?

-

Rafael: It is the hall.

-

Teacher: The hall? And, why have you taken a photo of this place?

-

Rafael: Because here you had, there you had the math problems, and then we build with Lego and other things.

-

Teacher: The girls could as well tell. You have taken pictures from same places. What have you learned here?

-

Alina: Nosotros have learned that you can't yell at that place. (Children from the half dozen-year-erstwhile age group, referring to the picture of the hallway with the walls covered with activities)

Category 2: Action

This category refers to learning experiences perceived by children from the actions they execute during their school routine. This category was identified by the verbs children used to depict their learning situations, and these verbs typically used when the children described pictures containing scenes—a combination of the place and the people nowadays (e.g., a classroom full of children during playtime).

-

Hither I learned to put shoes on. (Elias, five years former, referring to the movie of the entrance to the classroom).

-

I learned to wet myself in the water and take a shower. (João Paulo, 5 years old, referring to the picture show of children in the showers).

-

When I learned to eat there, I learned how to employ the fork and the knife …and still… when… to go to swallow. (Tomi, 5 years onetime, referring to the picture of children in the dining room).

-

And hither I have taken a photo of an ornamental leaf… I have learned to piece of work at the hobby and to make an decoration from leaves. (Laura, 5 years erstwhile, referring to the picture of her ain, handmade leaf ornamentation).

The deportment described by the children as learning situations were diverse—from descriptions straight related to the systematization of formal school knowledge (reading a book, counting, etc.) to situations that were associated with beingness at school and exploring the infinite (learning how to behave in the classroom or how to walk in the school'south corridors). Interestingly, play activities were similarly represented in both country's datasets, indicating that children tin identify learning in play.

In this item category, most of the differences in the children's descriptions were related to the country of origin. Brazilian children mainly expressed their perception of learning by referring to actions associated with daily collective and free activities: "I learned to slide" (Miguel, 5 years one-time, referring to the picture of the slide); "I learned to choose a juice" (Eloah, 5 years one-time, referring to the picture of the cafeteria). On the other paw, Finnish children described actions that were more related to systematized school activities: "I am… I am learning in the morn circumvolve to count to twenty" (Laura, 5 years onetime); "I accept also learned in the morning circle how to say the days" (Matti, iv years old); and "I have learned to look at the pictures: these pictures are nice, though I don't read." (Iiro, 4 years old).

Generally, the children'due south narratives most their learning through actions were shaped by a sense of time, highlighting the presence in time and learning as an instantaneous, experimental, sensitive, and sensory experience. The descriptions showed a connection betwixt learning and the novelty of doing something new, movements that involve others, and different opportunities to experience in space–time structure.

Category 3: Significant Others

Well-nigh of the pictures taken by the children mainly represented the concrete environment, such as indoor and outdoor places and the tools plant in these spaces. Information technology is noteworthy that the identify for children's learning is mainly the space where everyone is together: the classroom, the playground, the sandbox, and other spaces photographed and referred to by the children. However, interestingly, when the children reflected on the pictures of places and objects, they frequently referred to the people involved in the learning situations in these places. Thus, peers had the nigh significant role in the children's narratives; they were spoken of as having multiple roles (e.g., the part of a person who teaches or one who guides deportment) and different positions (due east.g., equally a proponent or a follower):

-

There (referring to the moving picture of the yard) is a day when I taught the girls to run faster. (Maria Eduarda, v years old).

-

She (referring to the peer) likewise teaches how to dance, isn't that correct, Maria Eduarda? (Ana Luiza, 5 years former).

The results in this category reveal a co-learning surroundings and an understanding of learning experience in which children recognize peers as models worth observing either in gratuitous activities or in adult-driven situations, such as morn circles or group discussions:

-

I draw and so desperately, but so desperately that my friends teach me how to do information technology right. (Maria Laura, 6 years old).

-

He takes my paw and I accept his, then I slide. (Miguel, five years old, explaining how he learned with a peer how to employ a slide).

-

Laura (five years old): I am…I am learning most the morning circles… how to count to twenty.

-

Teacher: Ahaa! Was there anyone with you when you learned?

-

Laura: All my friends.

The office of the adult was mentioned more frequently (twice as often) by the 6-yr-old groups; they related it mostly to someone who taught the rules. The word "no" was commonly used in association with the school'southward social rules—to explain what they could not practise in each specific environs, such as "I learnt not to throw sand at anybody with the teacher" (Isaias, 6 years onetime, referring to the rules in the sandbox). The only fourth dimension that the children explicitly associated the instructor with content they learned was when reflecting on a picture of the yard where the gymnastics class was ordinarily conducted. In this paradigm, the teachers appeared to exist explaining what the children were going to practise: "Teacher explains how we are going to play" (Ana Luiza, half dozen years old); or showing how the action is washed, "When I am with Fifty. (teacher), I acquire to exercise some exercises" (Ana Vitoria, 6 years old).

This category revealed that the children from all historic period groups perceived their learning experience at these two schools equally a process that occurred with and through other people, highlighting the function of peers as partners. The places or the objects in the pictures besides represented learning situations that were directly related to the relationships established with each infinite of the school. Thus, the meaning of the learning experience was only expressed when the children talked near how these moments were constituted and who composed the space.

Category four: Cultural Practices

In this written report, cultural practices refer to all the interactions and activities that organize and found schoolhouse life. While describing their learning experiences, children named some of these specific activities. Thus, this category captures children's perceptions of learning related to daily schoolhouse practices, such every bit morning time circles, playground time, instructor-directed activities, dressing up in the entrance hall, and having breakfast/dejeuner. The children connected certain learning experiences to specific places in which the daily practices occurred, indicating that they had clear and different expectations of learning, depending on specific practices and spaces. This is evident in the following dialog between the teacher and Anni, v years old:

-

Teacher: Let'south see from hither. What place is this?

-

Anni: From the morn circle.

-

Instructor: Yes. And what can you learn there?

-

Anni: You learn to calculate and… So to say the weekdays.

-

Teacher: Then, what is this place?

-

Anni: The resting room.

-

Teacher: What do you lot think you could learn hither?

-

Anni: Well, in that location y'all tin can learn the "by steps" lesson, considering, you learn different emotions there.

-

Teacher: Yep, you have gone through that. And this place is?

-

Anni: The centre room.

-

Teacher: Yes. And what do yous learn hither?

-

Anni: There you learn how to do paper crafts, and then, well, to practise finger marking.

-

Teacher: We take done that a lot.

Interestingly, in both the Finnish and Brazilian data, we noted that this connection between content, practice, and identify becomes clearer as the children go older. Past referring to certain practices and places, the children also referred to the norms or rules that framed the learning situations, and thus provided a context for the learning experiences. Expressions such equally "we accept learned that we can't yell there," (Isaias, 6 years erstwhile, referring to the pic of the corridor with the activities of the children displayed on the walls of the school entrance) reveal that the children internalized social behavioral rules as the content of learning and associated them with a certain practice of the school routine. Even though the teachers and children synthetic the rules jointly, and therefore the rules appeared contextualized in daily practice, the adults did not wait these practices to serve equally a context for learning situations among the children. In the post-obit excerpt, the teacher makes a conceptual difference betwixt learning and behaving, and past doing so, she also produces a culturally accustomed way of understanding learning:

-

Teacher: … well, practise yous learn any new things or issues in this morning circle?

-

Lenna: that you have to sit on the bench and have to exist silent

-

Instructor: But are y'all learning something? That is quite about behavior.

-

Lenna: I learned how to calculate. (Lenna, 6 years sometime)

The flow of the discussion reveals how the child changes her own interpretations and accommodates the teacher's understandings by referring to calculations every bit the focus of learning. The discussion illustrates the differences betwixt the child's and teacher's understanding about the focus of learning and the teacher's powerful position in defining how learning is conceptualized. These values, rules, and the power relation between the instructor and the child too appeared in different kinds of cultural regulation, where institutional orders are negotiated betwixt the teacher and children.

Discussion

The starting point of this study was recognizing the importance of children'south perceptions of their own learning experiences. We also causeless that to explore these perceptions, it was of import to understand learning every bit a fundamentally social phenomenon (Vygotsky 1979) that is intrinsically linked to a specific social context, space, and time. It is of import to remark that the questions that guided the discussions also situate children'south reflection, affording or constraining the themes discussed. These premises framed the investigation of how children perceive their learning experiences in ECEC and supported how we interpreted the results.

The written report showed that the children'south perceptions of learning are intimately continued to how they explore objects and places, indicating that children create opportunities to freely construct noesis based on their appropriation and multiple uses of objects. The relationship that children class with the objects in the schoolhouse context was an attribute that motivated united states to consider elements that are not necessarily part of the teachers' pedagogical resources (eastward.g., the taps in the toilet, shoes, or stairs). Each child signified these objects according to their own singular feel, which, on many occasions, involved transforming the functionality and purpose of the objects and applying of new meanings according to space and time. This shows that children non simply reproduce meanings just produce it; they practise not merely adapt to the modification and (co)construction of social values and norms, simply also influence them. This finding supports previous research that has shown how children are active co-constructers of culture (Corsaro 2003, 2005).

Further, children too perceived their learning experience every bit the actions that they executed in the schoolhouse infinite, and they identified these acts in progress as the content of learning. This acknowledgment of action equally a learning experience implies that, for children, the focus of the learning process is not learning about something (e.one thousand., near numbers, mathematics), merely rather learning how to execute something (e.chiliad., counting from one to 10). The importance of empirical experiences for the structure of cognition in the early years has been heavily discussed inside the historical–cultural theoretical framework since Vygotsky'south (2007, 2009) work. Elements such as motility, pretend play, and role-play have been the nigh pregnant activities for preschoolers (Amparo et al. 2006), and numerous works from the disciplines of psychology, instruction, and sociology address this topic and discuss its relation to children's development. A salient feature of this written report is that information technology asks the children to express the empirical grounds of their learning processes past giving them an opportunity to do so. Listening to the children is thus emphasized here as a primal methodological arroyo to organize pedagogical work with children, irrespective of their cultural and social background.

Despite existence exposed to all sorts of material for teacher-directed activities, children represented their learning experiences through pictures of objects, places, and scenes that were related to their free process of noesis construction. Their narratives evidenced that learning is e'er negotiated with those who share that item frame of time and space. Therefore, when identifying what elements children use to express their learning experiences, it is important to consider that children learn according to a timeframe adamant by themselves, regardless of the intentions of adults.

Through the children'southward narratives, we identified tactics (Certeau 1994) to use schoolhouse time and infinite in a singular dimension. While children recognize the limitations of time placed by adults, they all the same create their own daily schooling by touching and modifying these limitations via new actions, relationships, and even new possibilities to live the experience in infinite–fourth dimension. When the learning space is an arena for tactics, it can likewise exist seen as a Thirdspace (Soja 1996) and heterotopia (Foucault 1967). For Soja, heterotopia is an instance of the Thirdspace. In open up social spaces, children can negotiate alternative orders of learning and become agents of learning. The learning space is undefined—a space of tactics and a place to explore one'south identity outside defined learning routines (Kupiainen 2013). Thirdspace and heterotopia are alternative social ordering that help realize creative practices and construct learning in spatializing processes with peers and cultural objects (Soja 1996). In this sense, a learning space is and then a product of different subjectivities, relationships, and practices (Comber 2016), constructed in relation to other surrounding places and spaces, communities, and cultures. These relations are important and give directions to learning and teaching, and by understanding the learning space as a social product (Soja 1996), we recognize how children experience their learning across space in different ways.

Interestingly, in both the Finnish and Brazilian groups, the appearance (e.chiliad., the color of walls and details of toys or costumes) and the characteristics of objects and places (eastward.g., plastic or fabric dolls, wooden or plastic playgrounds) were never mentioned. This observation suggests that for the children, the almost significant elements of objects and places are the access to them and the opportunity to explore them freely, and nosotros recognize that the nature of the questions that children were asked in the interviews may not take elicited specific reflections on the appearance of objects.

When we move from debating children's perceptions and focus on the relations established by children between learning and the space in which they learn in ECEC contexts, the relevance of others (i.east., human beings) in the learning feel becomes evident. The children revealed that peers and teachers signify the school space and are an essential part of the learning experience; thus, they express an agreement of learning as a commonage process. Even when children refer to specific objects manipulated by them individually, the contextualization of the learning experience occurs by the recognition of the others that shared that situation of learning.

Although teachers inhabit the socially recognized role of "the ane that teaches," they did not seem to occupy a identify of privilege in the children's experiences in either country. In fact, that position belonged to the peers. Previous studies (Ferreira 2017; Ferreira et al. 2016) take arrived at similar findings, showing that fifty-fifty when children have an adult past their side, they can withal place peers as the reference point for different activities. Peer civilisation is mainly constructed by the sharing of meanings and the (co)construction of play repertoire between children (Corsaro 2003, 2005). In this report, the children not only referred to peers as a reference point only as well sought their voluntary and intentional aid for learning how to do something. Hence, when reflecting on their learning experiences, the children revealed an intentionality that is rarely recognized by adults in peer-learning situations.

Our analysis revealed how the children'southward narratives of learning were partly influenced past the cultural manuscript of the schoolhouse. By cultural manuscripts (Tan 2015; Gutierrez et al. 1995), we refer to the cultural values, assumptions, behavior, and their manifestation in the daily practices of the schools. The national-level regulation and steering documents, besides as broader cultural beliefs, partly influence the cultures of schools. However, each schoolhouse's civilisation is constructed by the everyday activities that involve teachers, children, and other staff members. Thus, given that all the described situations and narratives occurred and were synthetic in the actual school environment, it is possible to conclude that the schoolhouse is a infinite of learning allows the children to construct themselves and other children significantly in the learning procedure. The school culture does non enforce learning from a future-oriented perspective but allows them to learn in the here and now. In addition, the children are immune to apply both outdoor and indoor spaces as learning spaces.

Decision

The children'south narratives showed how learning implies activity, doing something to be experienced in the "here and at present," contextualized in their firsthand interest. This is a vital aspect of how the children in this study represented and constructed the meaning of their learning experiences every bit independent work, or as work that is different from an adult's teaching–learning intention. Children are agents of learning as well as producers of their own learning environment inside the ECEC settings (Vuorisalo et al. 2015). When we empathize learning equally intertwined with material objects, actions, meaning others, and cultural practices in social spaces—as relational and synthetic in private experiences—we can too see the learning environment as subject to reconstruction. This means that learning is embedded in the immediate relationships of surrounding materiality, teachers and peers as well as shaped past cultural practices, communities, and experiences of individuals (Comber 2016).

The implications of these finding relate to the possibility open for children to be invited to imagine, design, and make material changes in their learning environments in ECEC settings, as they recognized their own competence for learning, exploration of places, manipulation of objects, and transformation of their environment to potentiate new experiences. The study supports the statement that children must exist featured equally protagonists in their learning processes. This written report utilized the opportunity to listen to children'due south voices in two different countries, and given the results, nosotros await that teachers, experts in education, and other professionals involved in developing alternatives to potentiate learning may glean ideas to reflect upon their understanding of children'southward learning, as well as the role of peers and the various spaces within that learning.

References

-

Act on early childhood education and care 2018/540. Accessed September 21, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2018/2018/540.

-

Allen, Q. (2012). Photographs and stories: Ethics, benefits and dilemmas of using participant photography with Blackness middle-class male youth. Qualitative Research, 12(4), 443–458.

-

Amparo, D., Pereira, Thousand. A., & Almeida, Southward. (2006). O brincar e suas relações com o desenvolvimento. Psicologia Argumento, 24(45), 15–24.

-

Blackbeard, D., & Lindegger, G. (2007). Building a wall around themselves: Exploring adolescent masculinity and beggary with photo-biographical inquiry. Southward African Periodical of Psychology, 37(one), 25–46.

-

Burger, Grand. (2015). Effective early childhood intendance and teaching: Successful approaches and didactic strategies for fostering child development. European Early on Babyhood Teaching Research Journal, 23(five), 743–760.

-

Carvalho, A. M. A., Muller, F., & Sampaio, S. M. R. (2009). Sociologia da infância, psicologia do desenvolvimento e educação infantil: diálogos necessários [Sociology of childhood, developmental psychology and early on childhood: Necessary dialogs]. In F. Muller & A. M. A. Carvalho (Eds.), Teoria e prática na pesquisa com crianças, diálogos com William Corsaro (pp. 189–208). São Paulo: Cortez.

-

Certeau, Thousand. (1994). A Invenção do Cotidiano: Artes de fazer. Petrópolis: Vozes.

-

Clark, A. (2005). Listening to and involving young children: A review of research and practise. Early Child Evolution and Care, 175(six), 489–505.

-

Colliver, Y., & Fleer, Thou. (2016). I already know what I learned: Immature children's perspectives of learning through play. Early Child Evolution and Intendance, 186(10), 1559–1570.

-

Comber, B. (2016). Literacy, identify, and pedagogies of possibility. New York: Routledge.

-

Cook, T., & Hess, E. (2007). What the camera sees and from whose perspectives: Fun methodologies for engaging children in enlightening adults. Childhood, 14, 29–45.

-

Corsaro, West. (2003). We're friends, right? Within kid'southward culture. Washington: Joseph Henry Printing.

-

Corsaro, W. (2005). The sociology of childhood. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

-

Einarsdottir, J. (2005). Playschool in pictures: Children's photographs as a research method. Early Child Development and Intendance, 175(half-dozen), 523–541.

-

Emilson, A., & Folkesson, A.-M. (2004). Children's participation and instructor control. Early Child Development and Care, 176(3–4), 219–238.

-

Ferreira, J. M. (2017). Crianças com déficit intelectual e processos interacionais com pares na pré-escola: reflexões sobre desenvolvimento [Children with intellectual inability and their interactions in pre-schoolhouse: Discussing about human being development]. Doctoral thesis, Faculty of Philosophy and Scientific discipline, Doctoral Plan in Psychology, University of São Paulo.

-

Ferreira, J. M., Mäkinen, Chiliad., & de Amorim, Yard. S. (2016). Intellectual inability in kindergarten: Possibilities of development through pretend play. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 217, 487–500.

-

Foucault, M. (1967). Of other spaces, heterotopia (Trans., J. Miskoviec). Accessed February 9, 2018. Retrieved from http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/foucault1.pdf.

-

González-Rey, F. (2009). Questões teóricas eastward metodológicas nas pesquisas sobre aprendizagem. In M. A. Martinez & Yard. C. V. R. Tacca (Eds.), A Complexidade da Aprendizagem (pp. 123–151). Campinas: Alínea.

-

González-Rey, F. (2014). Ideias due east Modelos Teóricos na Pesquisa Construtivo-Interpretativa. In A. Thou. Martinez, M. Neubern, & V. D. Mori (Eds.), Subjetividade contemporânea: discussões epistemológicas e metodológicas (pp. 13–34). Campinas: Alínea.

-

Goodrich, J. M., Lonigan, C. J., & Farver, J. Thou. (2017). Impacts of a literacy-focused preschool curriculum on the early literacy skills of linguistic communication-minority children. Early Babyhood Inquiry Quarterly, twoscore(3), thirteen–24.

-

Gutierrez, K. D., Larson, J., & Kreuter, B. (1995). Cultural tensions on the scripted classroom: The values of the subjugated perspective. Urban Education, 29(four), 410–442.

-

Harcourt, D., & Mazzoni, V. (2012). Standpoints on quality: Listening to children in Verona, Italy. Australasian Journal of Early on Childhood, 37(2), 19–26.

-

Helal, S., & Weil-Barais, A. (2015). Cognitive determinants of early letter knowledge. European Early Childhood Pedagogy Inquiry Periodical, 23(1), 86–98.

-

Hietamäki, J., Kuusiholma, J., Räikkönen, E., Alasuutari, Thou., Lammi-Taskula, J., Repo, Grand., Karila, Grand., Hautala, P., Kuukka, A., Paananen, M., Ruutiainen, V., & Eerola, P. (2017). Varhaiskasvatus ja lastenhoitoratkaisut yksivuotiaiden lasten perheissä [Solutions on early childhood didactics and care in families with one-year-quondam children]. National Institute for Wellness and Welfare (THL). Discussion paper 24/2017. Helsinki, Finland.

-

INEP. (2016). Sinopse Estatística da Educação Básica. Brasília: Ministério da Educação e Cultura.

-

Kupiainen, R. (2013). Media and digital literacies in secondary school. New York: Pete Lang.

-

Landry, South. H., Zucker, T. A., Williams, J. M., Merz, E. C., Guttentag, C. 50., & Taylor, H. B. (2017). Improving school readiness of high-run a risk preschoolers: Combining high quality instructional strategies with responsive training for teachers and parents. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 40, 38–51.

-

Larkin, South. (2010). Metacognition in young children. Oxon: Routledge.

-

Larrosa, J. B. (2002). Notas sobre a experiência e o saber de experiência. Revista Brasileira de Educacão, 19, 20–28.

-

Loughlin, J. (2013). How photography as field notes helps in understanding the edifice the didactics revolution. Austrian Education Research, twoscore, 535–548.

-

Ministry of Instruction of Brazil. (1990). Childhood and Adolescent Statute: Law n. eight.069, 13th of July 1990. Brasília: Sleeping accommodation of Deputies.

-

Ministry of Education of Brazil. (1996). Law 9.394, 20 of December 1996, of Full general Guidelines for Basic Education. Brasilia: National Congress.

-

Ministry of Teaching of Brazil. (2006). Guidelines for early childhood institution infrastructure. Brasília: Secretary of Basic Pedagogy SEB.

-

Ministry of Education of Brazil. (2010). National curriculum guidelines for early on childhood education. Brasília: Secretary of Basic Pedagogy, SEB.

-

Ministry of Pedagogy of Brazil. (2016). National plan for education: Guidelines for monitoring and evaluation of municipal didactics. Brasília: Secretary of Basic Education, SEB.

-

Okasha, S. (2002). Philosophy of science: A very short introduction. England: Oxford University Press.

-

Pálmadóttir, H., & Einarsdóttir, J. (2016). Video observations of children'south perspectives on their lived experiences: Challenges in the relations between the researcher and children. European Early Childhood Pedagogy Research Periodical, 24(5), 721–733.

-

Powell, M. A., Graham, A., Taylor, N. J., Newell, S., & Fitzgerald, R. (2011). Building chapters for ethical research with children and immature people: An international research project to examine the ethical problems and challenges in undertaking research with and for children in unlike majority and minority world contexts, Dunedin. Dunedin: University of Otago Centre for Enquiry on Children and Families.

-

Rutanen, N., Amorim, K. Southward., Colus, 1000. Chiliad., & Piattoeva, N. (2014). What is best for the child? Early childhood education and intendance for children under three years of age in Brazil and Republic of finland. International Journal of Early Childhood, 46(2), 123–141.

-

Sant'Ana, R. B. (2010). Criança-sujeito; experiências de pesquisa com alunos de escola pública. In One thousand. P. R. de Souza (Ed.), Ouvindo Crianças na escola: Abordagens qualitativas e desafios metodológicos para a psicologia (pp. 23–l). São Paulo: Casa exercise Psicólogo.

-

Santos, A. A. (2010). Construindo modos de conversar com crianças sobre suas produções escolares [Talking to children well-nigh their schoolhouse activities]. In M. P. R. Souza (Ed.), Ouvindo crianças na escola (pp. 203–228). São Paulo: Casa exercise Psicólogo.

-

Simões, P. G. U., & Lima, J. B. (2016). Infância, educação due east desigualdade no Brasil [Babyhood, pedagogy and social inequality in Brazil]. Revista Iberoamericana de educación, 72, 45–64.

-

Soja, Eastward. (1996). Thirdspace: Journey to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Cambridge: Blackwell.

-

Tan, C. (2015). Education policy borrowing and cultural scripts for instruction in Communist china. Comparative Education, 51(ii), 196–211.

-

Thinker, P. (2013). Using photographs in social and historical research. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

-

Trautwein, C., & Goncalves, T. (2010). A dor eastward a delícia de entrevistar crianças na construção de um procedimento [The gain and the pain to interview children within the construction of a process]. In K. P. R. de Souza (Ed.), Ouvindo Crianças na escola: Abordagens qualitativas e desafios metodológicos para a psicologia (pp. 257–278). São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo.

-

Vuorisalo, M., Rutanen, N., & Raittila, R. (2015). Constructing relational infinite in early on childhood education. Early on Years: An international journal of research and development, 35(i), 67–79.

-

Vygotsky, L. S. (1979). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological process. Cambridge: Harvard Academy Printing.

-

Vygotsky, Fifty. S. (2007). A formação social da mente: o desenvolvimento dos processos psicológicos superiores. [Mind in social club: The development of Higher Psychological Process]. São Paulo: Martins Fontes.

-

Vygotsky, L. Due south. (2009). Imaginação east criação na infância [Imagination and inventiveness in childhood]. São Paulo: Ática.

Acknowledgements

The study was conducted with the financial and infrastructure back up from the Federal Academy of Uberlândia and Tampere Academy.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We hither land that throughout the development and finalization of this piece of work at that place were no situations involving financial and personal relationships that could inappropriately influence (bias) this work. Therefore, we declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original writer(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferreira, J.Grand., Karila, M., Muniz, L. et al. Children's Perspectives on Their Learning in School Spaces: What Can We Learn from Children in Brazil and Finland?. IJEC 50, 259–277 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-018-0228-six

-

Published:

-

Issue Appointment:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1007/s13158-018-0228-6

Keywords

- Learning spaces

- Children's perceptions

- Cultural practices

- Multicultural research

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13158-018-0228-6

Posted by: rolandindread.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Sort Of Perspectives Are We Born With Compared To The Ones That Are Learned"

Post a Comment